A team of chemical engineers has developed a new way to produce medicines and chemicals on demand and preserve them using portable “biofactories” embedded in water-based gels called hydrogels.

The approach could help people in remote villages or on military missions, where the absence of pharmacies, doctor’s offices or even basic refrigeration makes it hard to access critical medicines, daily use chemicals and other small-molecule compounds.

Led by Hal Alper, Professor at The University of Texas (UT) at Austin’s Cockrell School of Engineering, in collaboration with chemist Alshakim Nelson and his research group at the University of Washington, this first-of-its-kind system effectively embeds microbial biofactories — cells bioengineered to overproduce a product — into the solid support of a hydrogel, allowing for portability and optimised production.

We have taken a completely different angle for fermentation by utilising hydrogels

Medicines such as antibiotics have a certain shelf life and require particular storage conditions. The portability of the biofactory to make these molecules makes the hydrogel system especially useful in remote places, without access to refrigeration to store medications.

Published in Nature Communications, the report explains that the new technology would also be a small and compact way to maintain access to several medications and other essential chemicals when there is no access to a pharmacy or a store, like during a military mission or a mission to Mars. Although not quite there yet, the possibilities are promising.

This is the first hydrogel-based system to organise both individual microbes and consortia for in-the-moment production of high-value chemical feedstocks, used for processes such as fuel production, and pharmaceuticals. Products can be produced within a couple of hours to a couple of days.

All UT investigators involved with this research have filed their required financial disclosure forms with the university. Alper and his team have filed a provisional patent and are working with UT’s Office of Technology Commercialisation to license the technology.

Products can be produced within a couple of hours to a couple of days

“We have taken a completely different angle for fermentation by utilising hydrogels,” said Alper, whose research expertise is focused in biotechnology and cellular engineering. “Many of the chemicals, fuels, nutraceuticals and pharmaceuticals we use rely on traditional fermentation technology.”

He explained that their new technology addresses a strong limitation in the fields of synthetic biology and bioprocessing, namely the ability to provide a means for both on-demand and repeated-use production of chemicals and antibiotics from both mono- and co-cultures.

Small molecules to proteins

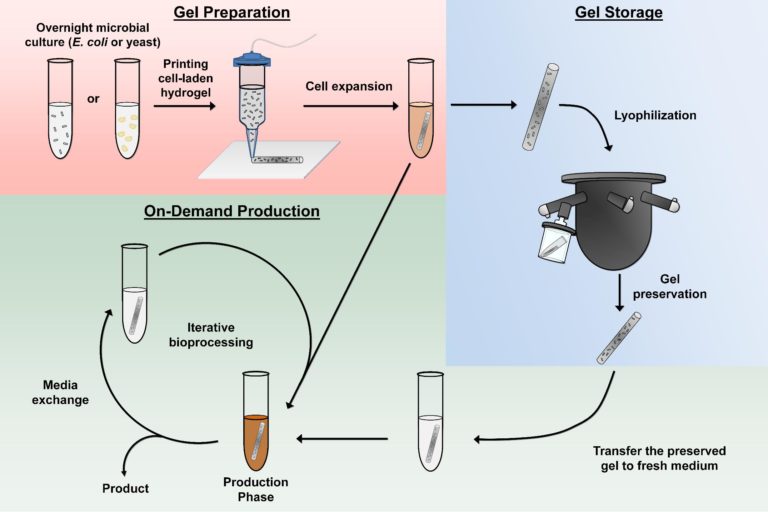

As a crosslinked polymer, the hydrogel used in this work can be 3D printed or manually extruded. The gel material, along with the cells inside, can flow like a liquid and then harden upon exposure to UV light. Molecularly, the resulting polymer network is large enough for molecules and proteins to move through it, but the space is too small for cells to leak out.

The team also found that by lyophilising, or freeze-drying, the hydrogel system, it can effectively preserve the fermentation capacity of the biofactories until needed in the future. The result of the freeze-drying somewhat resembles an ancient mummy, shrivelled up but well-preserved. To revive the hydrogel and enable the production of the chemical or pharmaceutical, one would simply add water, sugar and/or some other basic nutrients, and the cells will then convert into the product just as effectively as before the preservation process.

Image as seen on Texas University website

One of the novel aspects enabled by this platform is the ability to combine multiple different organisms, called consortia, together in a way that outperforms traditional, large-scale bioreactors. In particular, this system enables a plug-and-play approach to combining and optimising chemical production.

For example, if one set of enzymes works best in the bacteria E. coli, while the other works best in the yeast S. cerevisiae, the two organisms can work together to more efficiently go straight to the product. The research team tested both of these organisms.

This platform has the added benefit of multitasking, keeping different types of cells separated while they grow, preventing one from taking over and killing off the others. Likewise, by testing a range of temperatures, the team was able to control the dynamics of the system, keeping the growth of multiple cell types balanced.

Finally, the team was able to show continuous, repeated use of the system (with yeast cells) over the course of an entire year without a decrease in yields, indicating the sustainability of the process over time.