The immune system is a complex, finely tuned network of cells, organs and proteins. It plays a vital role by fighting off foreign invaders such as viruses, bacteria and other pathogens.

A strong immune system is balanced, functional and ready to launch a robust, targeted response when needed. It then quickly stands down to prevent self-damage.1

We can help to maintain a healthy immune system by optimising and supporting its function.

This becomes particularly important in situations when the immune system is likely to be under stress or compromised. Chronic psychological stress can increase inflammation, which lowers the immune system’s ability to respond effectively to threats.2

Supporting immunity is also essential during seasonal and high-exposure times, such as when travelling, in professionally stressful situations and in winter, when the body has to fight off more infections.

Chronic conditions such as obesity or diabetes can also impair immune function.3 As we age, the immune response naturally becomes less robust — a process called immunosenescence.4

Consistent healthy lifestyle habits, including proper nutrition, adequate sleep and regular exercise, provide a foundational support to optimise immune health.5

How Pycnogenol supports healthy immune function

Pycnogenol, as part of a healthy diet, provides targeted support to maintain balanced immune activity. This helps the body to regulate inflammation and oxidative stress — two key drivers of immune resilience.

Symptoms of infectious diseases, such as the common cold, allergies, asthma and autoimmune conditions, have all been reduced with Pycnogenol.

Controlled inflammation

Inflammatory processes are key mechanisms in the immune response; they react to infective agents and repair affected tissue. However, there are certain instances when what was actually a protective reaction causes inflammation and can lead to certain pathologies.6

This occurs when the response either overshoots or fails to be naturally resolved by internal anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

Inflammaging, for example, is a chronic, low-grade inflammation that can develop with age and subsequently contributes to age-related diseases and a decline in health.7

Furthermore, the immune system may mistakenly target the body’s own cells or inappropriately react to harmless substances. This can lead to long-lasting chronic inflammation, autoimmune diseases and allergic reactions, which damage the cells and tissues of the body.

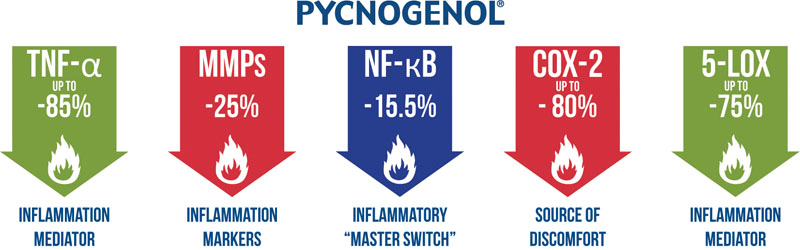

Pycnogenol’s potent anti-inflammatory properties help explain its modulatory effects on the immune system.8–12

This pine bark extract has been shown to normalise immune responses by attenuating general inflammation.

Intake of Pycnogenol was shown to significantly limit the activation of the proinflammatory “master switch” NF-kB by 15.5% and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) release by 25%.8

These are two important regulators in the inflammation process. This positive effect helps to prevent the mobilisation of proinflammatory molecules.

In another study, Pycnogenol significantly prevented the up-regulation of the proinflammatory enzymes 5-LOX and COX-2 after only 5 days of daily intake.9

Furthermore, the consumption of a single 300 mg dose of Pycnogenol was found to naturally inhibit the activity of the enzyme COX-2 during inflammation, providing a significant contribution to lowering discomfort.10

In addition, a statistically significant inhibition of inflammatory molecules COX-1 and COX-2 was observed after Pycnogenol intake.10

These effects were confirmed in a study with immune cells (macrophages) that are involved in allergic reactions.11 Pycnogenol significantly decreased the elevated production of inflammation markers IL-1 β and IL-6, as well as MMP-9 in a dose-dependent manner.

In a similar study, Pycnogenol suppressed the upregulation of inflammation markers and blocked the activation of an allergy related pathway in cells of the inner layer of lungs (airway epithelial cells) that had been treated with an allergen.12

Beyond inflammation control, Pycnogenol also delivers strong antioxidant protection, another foundational pillar of immune health.

Powerful antioxidant

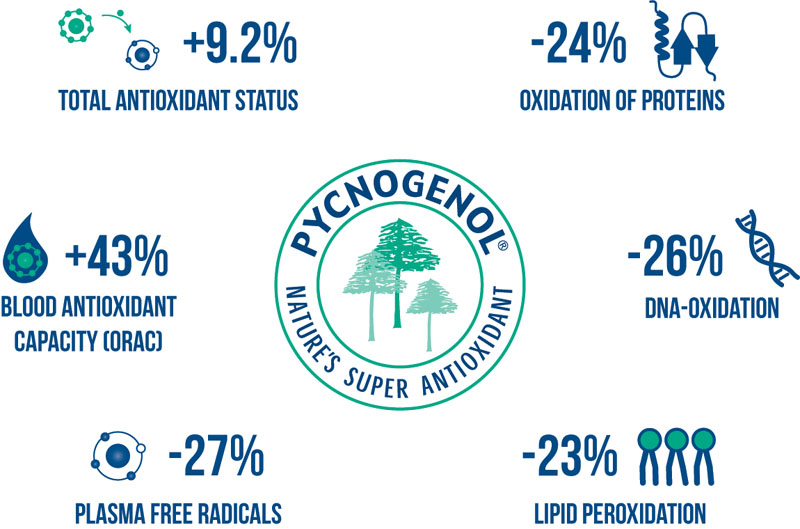

Pycnogenol has been investigated in various clinical studies and shown to possess potent antioxidant properties.13–20

When taken orally, Pycnogenol has been shown to both increase plasma antioxidant capacity — also expressed as oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) — and decrease plasma oxidative stress (measured as plasma free radicals).13–16

Pycnogenol has further been shown to protect various essential molecules, such as proteins, DNA and lipids, from oxidative damage.

Protein oxidation (measured as advanced oxidation protein products) was shown to be reduced with Pycnogenol.17 The protective effects of Pycnogenol on DNA oxidation were shown in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of children with ADHD by measuring oxidised purines.18

Lipid peroxidation by free radicals in elderly people and people with coronary artery disease was reduced after Pycnogenol intake.19,20

Taken together, these findings illustrate how Pycnogenol’s dual action — modulating inflammatory pathways and reducing oxidative stress — helps to maintain balanced immune function across a variety of everyday challenges.

Clinical evidence in immune-related conditions

Improved symptoms of the common cold: Infectious diseases, caused by pathogens such as viruses, bacteria or fungi, attack the body from the outside and challenge the immune system.

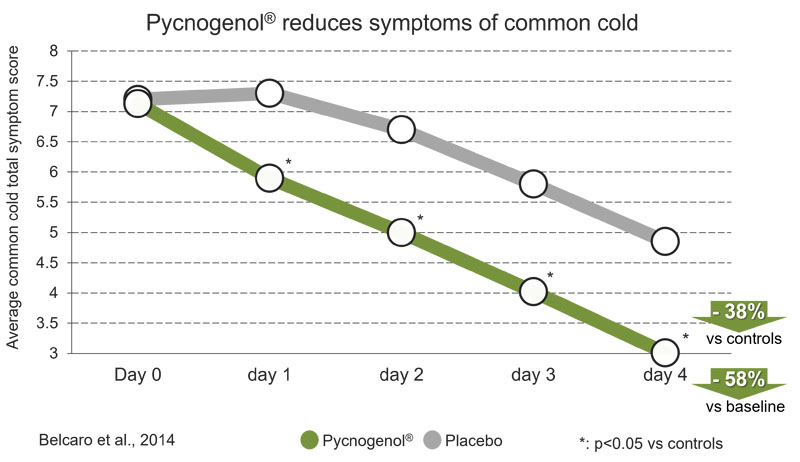

One of the most familiar infections in the wintertime is the common cold. In two studies, Pycnogenol was shown to decrease both signs and symptoms of the common cold and shorten recovery times (with or without well-known immunity supporters zinc and vitamin C).21,22

The studies showed that symptoms such as runny nose, nasal obstruction, sore throat, sneezing, high temperature, cough, headache, and general discomfort were reduced by 58% (compared with baseline) and 38% (compared with controls), respectively.

The need for treatments such as nasal drops, pain medication or fever-reducing agents was reduced with the supplement. Pycnogenol intake also limited the sickness days to 4 (maximum) and reduced the number of lost working days.21,22

Amelioration of other symptoms: Pycnogenol was also shown to have beneficial effects on symptoms of other infectious conditions by helping the immune system to cope with inflammation and oxidative stress.

Recently, it was shown that Pycnogenol intake has beneficial effects on the signs, symptoms and frequency of recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs).23,24

The number of UTI episodes within 2 months was significantly lower with Pycnogenol than in control patients; interestingly, it was even lower compared with patients taking traditionally used cranberry extract.

Another study showing Pycnogenol’s beneficial effects on infection-related symptoms was conducted with people with a history of Lyme disease.25

Inflammation and high oxidative stress in these subjects were relieved with Pycnogenol, which reduced the number of corticosteroids needed and the intensity of the perceived symptoms.

References

- S. McComb, et al., Methods Mol. Biol. 2024, 1–24 (2019).

- S.C. Segerstrom, et al., Psychol. Bull. 130(4), 601–630 (2004).

- G.S. Hotamisligil, Nature 542(7640), 177–185 (2017).

- Y. Wang, et al., Frontiers in Immunology 13, 942796 (2022).

- www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/how-to-boost-your-immune-system.

- M. Fioranelli, et al., Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(10), 5277 (2021).

- L. Ferrucci, et al., Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 15(9), 505–522 (2018).

- T. Grimm, et al., J. Inflamm. (Lond.) 3,1 (2006).

- R. Canali, et al., Int. Immunopharmacol. 9(10), 1145–1149 (2009).

- A. Schäfer, et al., Biomed. Pharmacother. 60(1), 5–9 (2005).

- I.S. Shin, et al., Food Chem. Toxicol. 62, 681–686 (2013).

- Z. Liu, et al., DNA and Cell Biology 35, 1–10 (2016).

- H.M. Yang, et al., Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 86(8), 978–985 (2007).

- Z. D̆uračková, et al., Nutrition Research 23(9), 1189–1198 (2003).

- S. Devaraj, et al., Lipids 37(10), 931–934 (2002).

- G. Belcaro, et al., Minerva Medica 104(4), 439–446 (2013).

- M. Kolacek, et al., Free Radic. Res. 47(8), 624–634 (2013).

- Z. Chovanova, et al., Free Radic. Res. 40(9), 1003–1010 (2006).

- J. Ryan, et al., J. Psychopharmacol. 22(5), 553–562 (2008).

- F. Enseleit, et al., Eur. Heart J. 33(13), 1589–1597 (2012).

- G. Belcaro, et al., Otorinolaringol. 63, 151–161 (2013).

- G. Belcaro, et al., Panminvera Med. 56, 301–308 (2014).

- R. Cotellese, et al., Panminerva Med. 63(3), 343–348 (2021).

- A. Ledda, et al., Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2021, 9976299 (2021).

- M.R. Cesarone, et al., Minerva Med. 116(3), 188–194 (20250.